They’re everywhere: bus wrappers, television, radio, billboards and stickers on the local newspaper. Yes, you guessed it — I’m referring to ads for plaintiff’s attorneys.

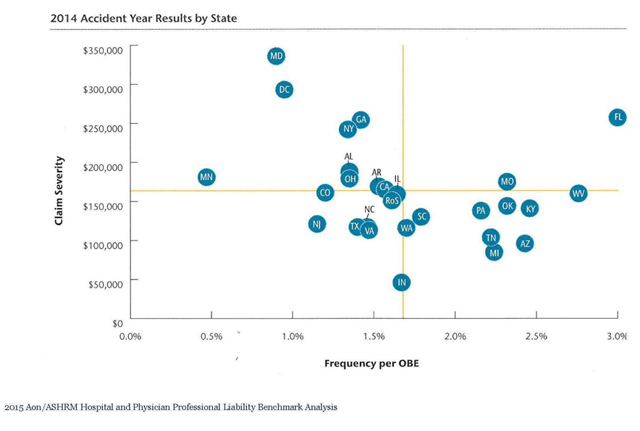

A few weeks ago, I was in a hotel where there was an old-fashioned yellow pages with several tear-away strips on the cover informing me that a named attorney, with a toll-free telephone number, would give me free consultation in home or hospital for “all types of accidents and medical malpractice.” The logo of a speeding car left me in no doubt that a lawyer could be with me in a moment’s notice. His sticky advertisement promised: “We stick with you.” No doubt, our nation should have a fair system in which patients who develop significant complications from negligent medical care should receive appropriate compensation. From the vantage point of health care professionals doing their best to help patients, however, the idea of lawyers soliciting potential litigants who experience a complication is irritating to say the least. In Florida, the environment for litigation involving health care claims is the worst in the nation. This can be seen in the graph below, which shows data by state for the year 2014. The X axis is the frequency of malpractice claims per hospital bed (technically per “OBE” or “Occupied Bed Equivalent — a standard measure of overall professional liability risk) and the Y axis is the average dollar amount paid per claim (“average severity”). The total expenditure on malpractice claims per hospital bed can be thought of as claim frequency times average severity. The bottom left quadrant shows states with low average severity and low claim frequency. Florida can be seen in the upper right quadrant, with claim frequency and average severity that are both the highest in the nation. Where expenditures on malpractice claims per bed are high, it stands to reason that professional liability insurance premiums would also be high. In Florida, insurance premiums have risen to levels such that many physicians in certain fields, such as obstetrics and neurosurgery, simply can’t afford the premiums and “go bare.” That is certainly a risky — and stressful — way to practice medicine! And there are also personal implications, such as living one’s life without being able to accumulate assets. That is, to avoid having significant financial assets that can be recovered in a lawsuit, many physicians who practice without insurance coverage pour a disproportionate share of their assets into a home (which is subject to legal protections against recovery in settlements or jury verdicts) and transfer remaining assets to others, such as their spouse. Listen to the president of a major medical association: “Tort law reform is a crucial issue…and it would not be an overstatement to say that the situation has reached the boiling point. Over the past 18 months there has been a growing chorus of calls for the AMA to work with government to do something to address the blow-out in medical indemnity premiums. We have reached a situation where clinicians in a number of fields are obliged to carry an unrealistic premium burden. This cannot be sustained on a long-term basis.” Of note is that the above quotation is taken from a speech a few years back given by the president of the Australian Medical Association. Professional liability for health professionals has become a problem in every part of the world where the common law system of recovery for torts (civil wrongs) brings doctors and lawyers into litigious conflict.

The plaintiff’s bar, of course, has a different viewpoint. High malpractice premiums do not reflect a large number of claims brought by patients solicited by plaintiff lawyers, nor by high jury awards, nor by the absence of caps on verdicts, but rather are due to the imposition of higher malpractice premiums by insurance companies to make up for low investment performance. As an example of this thinking, here is an excerpt from a 2003 speech given by Alfred Carlton Jr., then president of the American Bar Association: “The fact is, a 50-year review of the investment cycle indicates that every time investment returns decline, (malpractice) insurance premiums increase. The fact is, there is no credible evidence available to demonstrate any variable other than investment returns that affects insurance premiums.” As you can imagine, statements from the Trial Lawyers Association are along similar lines, but more vitriolic.

When a significant complication occurs in medical practice, doctors, lawyers, patients and their families bring different perspectives to the episode. Patients who suffer from a significant medical complication as a result of negligent care should be compensated appropriately. Every case has its own complexities, and all parties have understandable concerns from their vantage point. Complex problems rarely yield simple solutions. Nationally, there are ongoing debates about a variety of approaches. Locally, however, we must deal with the realities of the current system in real time. Over the past 45 years, the University of Florida has developed a self-insurance program (“SIP”) for professional liability that is a model for the nation. In the July 28, 2011 edition of OTSP, titled “Improving Patient Care and Reducing Medical Liability Litigation Using Pre-Suit Mediation,” I presented the early mediation component of SIP. In this newsletter, you will learn more about the history, milestones and future plans of this remarkable program.

Listen to the president of a major medical association: “Tort law reform is a crucial issue…and it would not be an overstatement to say that the situation has reached the boiling point. Over the past 18 months there has been a growing chorus of calls for the AMA to work with government to do something to address the blow-out in medical indemnity premiums. We have reached a situation where clinicians in a number of fields are obliged to carry an unrealistic premium burden. This cannot be sustained on a long-term basis.” Of note is that the above quotation is taken from a speech a few years back given by the president of the Australian Medical Association. Professional liability for health professionals has become a problem in every part of the world where the common law system of recovery for torts (civil wrongs) brings doctors and lawyers into litigious conflict.

The plaintiff’s bar, of course, has a different viewpoint. High malpractice premiums do not reflect a large number of claims brought by patients solicited by plaintiff lawyers, nor by high jury awards, nor by the absence of caps on verdicts, but rather are due to the imposition of higher malpractice premiums by insurance companies to make up for low investment performance. As an example of this thinking, here is an excerpt from a 2003 speech given by Alfred Carlton Jr., then president of the American Bar Association: “The fact is, a 50-year review of the investment cycle indicates that every time investment returns decline, (malpractice) insurance premiums increase. The fact is, there is no credible evidence available to demonstrate any variable other than investment returns that affects insurance premiums.” As you can imagine, statements from the Trial Lawyers Association are along similar lines, but more vitriolic.

When a significant complication occurs in medical practice, doctors, lawyers, patients and their families bring different perspectives to the episode. Patients who suffer from a significant medical complication as a result of negligent care should be compensated appropriately. Every case has its own complexities, and all parties have understandable concerns from their vantage point. Complex problems rarely yield simple solutions. Nationally, there are ongoing debates about a variety of approaches. Locally, however, we must deal with the realities of the current system in real time. Over the past 45 years, the University of Florida has developed a self-insurance program (“SIP”) for professional liability that is a model for the nation. In the July 28, 2011 edition of OTSP, titled “Improving Patient Care and Reducing Medical Liability Litigation Using Pre-Suit Mediation,” I presented the early mediation component of SIP. In this newsletter, you will learn more about the history, milestones and future plans of this remarkable program.

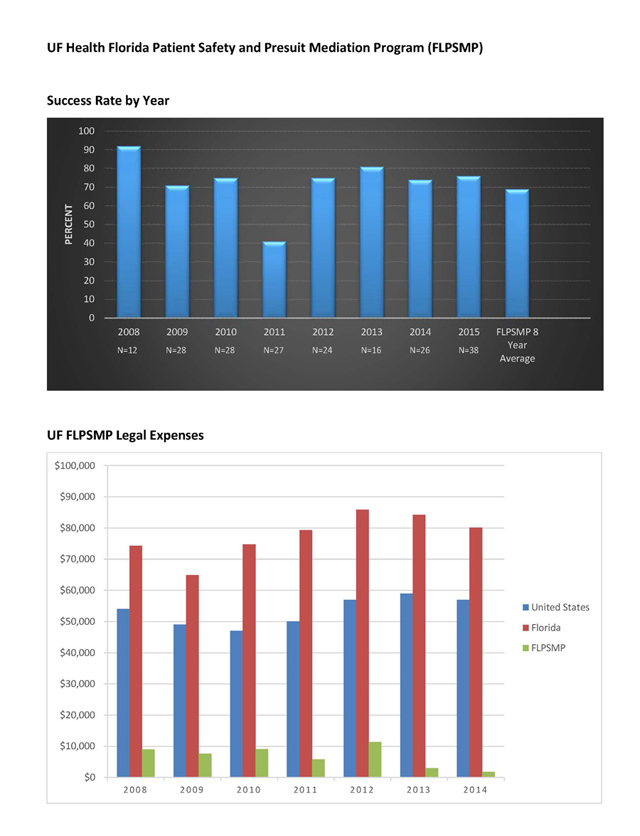

UF SIP has managed to keep premiums affordable because providers and administration let SIP know about possible exposures in real time. Timely reporting allows SIP to resolve potential claims proactively, well before a lawsuit, nearly 70 percent of the time. In fact, the UF pre-suit mandatory mediation program, or FLPSMP, launched in 2008 resolves claims within six months and without the 56 percent to 78 percent of each indemnity dollar consumed by legal fees and costs in traditional litigation. Thus, FLPSMP averages $6,911 in legal expenses to resolve a claim, compared with the state of Florida average defense cost of $80,100. UF SIP has used FLPSMP to help reduce SIP annual legal expenses by about $1 million. (See FLPMSP graphs).

UF SIP is involved in many other areas, outside the scope of this newsletter, where SIP helps current and past UF Health providers. For example, the underwriting and insurance professionals within SIP issue over 4,000 certificates of protection, coverage confirmations and claim history requests to providers and requesting institutions each year. Also, our education and loss prevention professionals contribute to peer-reviewed journals regularly and taught 100 in-person medical legal lectures this past year. The SIP lecture of how to disclose an event continues to be a favorite. During the past year over 1,200 SIP providers received the free continuing education benefit of online SIP medical legal training courses and an additional 600 health care providers from all over the USA learned from SIP online training. Perhaps most importantly, SIP partners with its participants to continually improve through programs such as patient safety organizations and the Smith loss prevention patient safety grant programs.

As word spreads about UF SIP results, others have asked SIP to help them develop a SIP or for help replicating a piece of the UF SIP. Because of the strong UF Health leadership support, SIP staff are the starting point for these accomplishments. The dedicated staff help patients and providers during some of their toughest life moments. SIP phone calls rarely bring good news. But much like UF SIP history, SIP works to foster good things from difficult experiences. Florida laws and rules governing SIP further help by protecting the SIP-provider conversations and materials with strict confidentiality for perpetuity. This confidentiality promotes candor, important evaluation and reflection, and if appropriate, resolution. A solvent self-insurance program timely resolves meritorious claims while powerfully defending unavoidable complications patients experience. A solvent and successful self-insurance program balances these competing perspectives while supporting the dejected health care providers who suffer along with their patient. These often unpredictable complications happen to all of us in life. The UF SIP history, challenges and successes remind all of us how adversity, when handled the right way, helps us emerge stronger than ever.

The Power of Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Vice President, Health Affairs

President, UF Health

To View This Article and More Click Here.

UF SIP has managed to keep premiums affordable because providers and administration let SIP know about possible exposures in real time. Timely reporting allows SIP to resolve potential claims proactively, well before a lawsuit, nearly 70 percent of the time. In fact, the UF pre-suit mandatory mediation program, or FLPSMP, launched in 2008 resolves claims within six months and without the 56 percent to 78 percent of each indemnity dollar consumed by legal fees and costs in traditional litigation. Thus, FLPSMP averages $6,911 in legal expenses to resolve a claim, compared with the state of Florida average defense cost of $80,100. UF SIP has used FLPSMP to help reduce SIP annual legal expenses by about $1 million. (See FLPMSP graphs).

UF SIP is involved in many other areas, outside the scope of this newsletter, where SIP helps current and past UF Health providers. For example, the underwriting and insurance professionals within SIP issue over 4,000 certificates of protection, coverage confirmations and claim history requests to providers and requesting institutions each year. Also, our education and loss prevention professionals contribute to peer-reviewed journals regularly and taught 100 in-person medical legal lectures this past year. The SIP lecture of how to disclose an event continues to be a favorite. During the past year over 1,200 SIP providers received the free continuing education benefit of online SIP medical legal training courses and an additional 600 health care providers from all over the USA learned from SIP online training. Perhaps most importantly, SIP partners with its participants to continually improve through programs such as patient safety organizations and the Smith loss prevention patient safety grant programs.

As word spreads about UF SIP results, others have asked SIP to help them develop a SIP or for help replicating a piece of the UF SIP. Because of the strong UF Health leadership support, SIP staff are the starting point for these accomplishments. The dedicated staff help patients and providers during some of their toughest life moments. SIP phone calls rarely bring good news. But much like UF SIP history, SIP works to foster good things from difficult experiences. Florida laws and rules governing SIP further help by protecting the SIP-provider conversations and materials with strict confidentiality for perpetuity. This confidentiality promotes candor, important evaluation and reflection, and if appropriate, resolution. A solvent self-insurance program timely resolves meritorious claims while powerfully defending unavoidable complications patients experience. A solvent and successful self-insurance program balances these competing perspectives while supporting the dejected health care providers who suffer along with their patient. These often unpredictable complications happen to all of us in life. The UF SIP history, challenges and successes remind all of us how adversity, when handled the right way, helps us emerge stronger than ever.

The Power of Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Vice President, Health Affairs

President, UF Health

To View This Article and More Click Here.